On Tuesday, March 22, Lidya Sitohang (Co-supervised by Dr Lothar Smith and Dr Martin van der Velde) successfully defended her PhD thesis on ‘Cross-border interaction in the context of development in the Indonesian-Malaysian border region’. A thesis in which she nicely shows, that places are more than just ‘bordered’ regions and that in these places, people are making a living and in their everyday cross-border interactions are the source for development of the region. Also, these examples of everyday border crossings show again that we as human beings are always already beyond our own borders. An

On Tuesday, March 22, Lidya Sitohang (Co-supervised by Dr Lothar Smith and Dr Martin van der Velde) successfully defended her PhD thesis on ‘Cross-border interaction in the context of development in the Indonesian-Malaysian border region’. A thesis in which she nicely shows, that places are more than just ‘bordered’ regions and that in these places, people are making a living and in their everyday cross-border interactions are the source for development of the region. Also, these examples of everyday border crossings show again that we as human beings are always already beyond our own borders. An  issue which I regularly refer to also on this blogsite, both in theoretical and philosophical terms as well as in more empirical terms. Especially her subtitle beautifully expresses the embodiment of cross-border interaction: ‘Garuda is on my chest, but my stomach is in Malaysia’.

issue which I regularly refer to also on this blogsite, both in theoretical and philosophical terms as well as in more empirical terms. Especially her subtitle beautifully expresses the embodiment of cross-border interaction: ‘Garuda is on my chest, but my stomach is in Malaysia’.

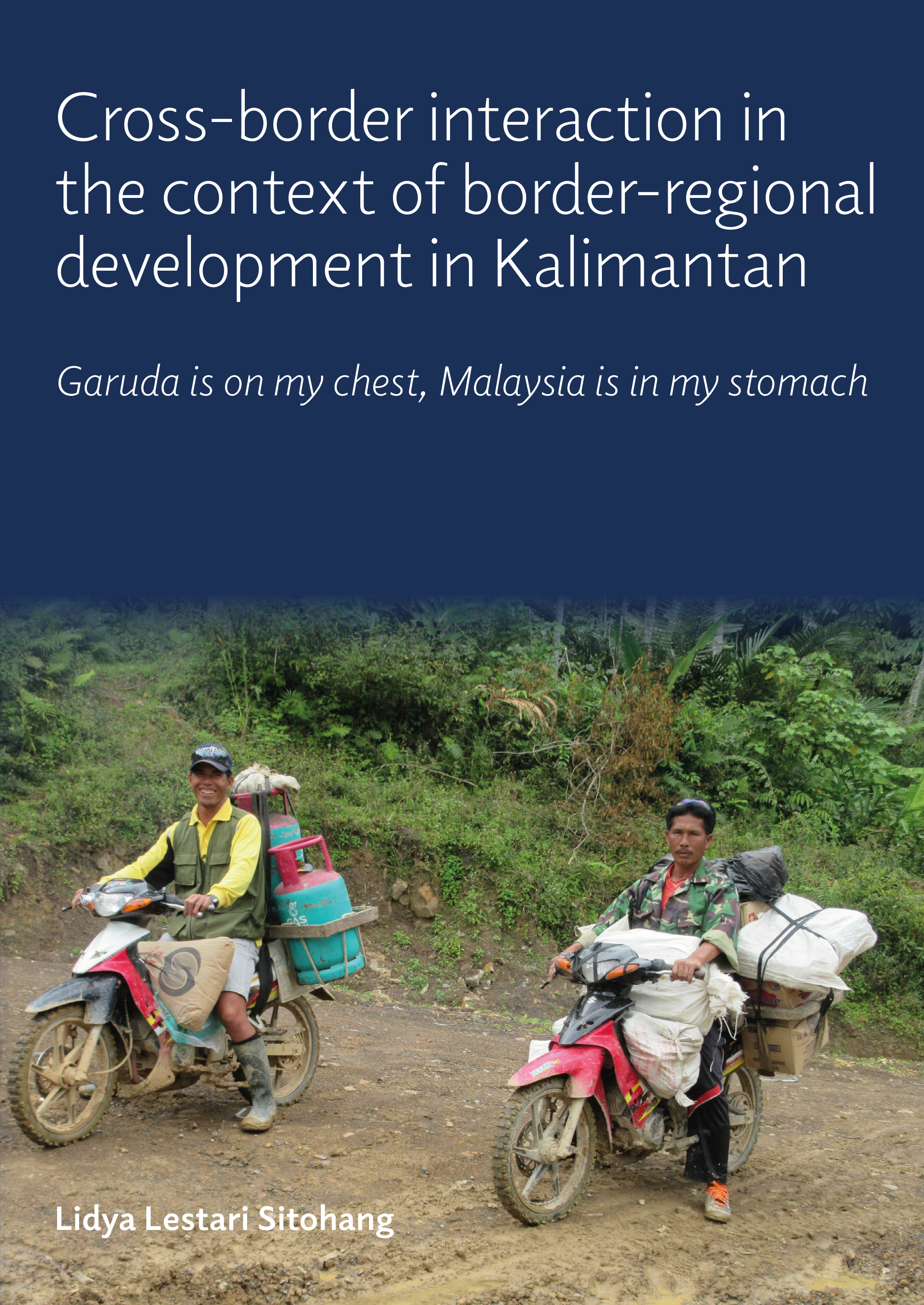

To quote her summary (click on picture to the right to download the full PhD Thesis): ‘This study investigates the border crossing of Krayan’s locals into Malaysia as a means of meeting their daily needs, which cannot be met in Krayan because of the poor state of development of the region. People living in the more central areas of Indonesia tend to regard the Krayan locals’ border crossing into Malaysia as a sign of decreasing loyalty, and hence a lack of nationalistic pride, towards the State of Indonesia. In contrast, the Krayan locals feel that their sense of nationalism and loyalty to the State of Indonesia is proven through their persistent wish to live in an area at the very edge of the country’s territory, regardless of the lack of development in Krayan. Living on the border with Malaysia, the locals see themselves as guardians of the sovereign territory of the Republic of Indonesia. Another factor is that in Krayan border crossing has long been part of life and existed prior to the formation of the two states. Crossing the border into Malaysia continues to be a matter of visiting family members, where ‘family’ includes all individuals who have a common cultural background and live on either side of the border. Also, as the respondents explained, the poor development in the region forces them to go to Malaysia and this does not compromise their loyalty to the State of Indonesia. The locals mentioned the expression Garuda di dadaku, tapi Malaysia di perutku (Garuda is on our chest, but our stomach is Malaysia), which aptly depict that they hold Indonesia in their hearts even though their livelihoods are supported by Malaysia’ (p. 260).

To quote her summary (click on picture to the right to download the full PhD Thesis): ‘This study investigates the border crossing of Krayan’s locals into Malaysia as a means of meeting their daily needs, which cannot be met in Krayan because of the poor state of development of the region. People living in the more central areas of Indonesia tend to regard the Krayan locals’ border crossing into Malaysia as a sign of decreasing loyalty, and hence a lack of nationalistic pride, towards the State of Indonesia. In contrast, the Krayan locals feel that their sense of nationalism and loyalty to the State of Indonesia is proven through their persistent wish to live in an area at the very edge of the country’s territory, regardless of the lack of development in Krayan. Living on the border with Malaysia, the locals see themselves as guardians of the sovereign territory of the Republic of Indonesia. Another factor is that in Krayan border crossing has long been part of life and existed prior to the formation of the two states. Crossing the border into Malaysia continues to be a matter of visiting family members, where ‘family’ includes all individuals who have a common cultural background and live on either side of the border. Also, as the respondents explained, the poor development in the region forces them to go to Malaysia and this does not compromise their loyalty to the State of Indonesia. The locals mentioned the expression Garuda di dadaku, tapi Malaysia di perutku (Garuda is on our chest, but our stomach is Malaysia), which aptly depict that they hold Indonesia in their hearts even though their livelihoods are supported by Malaysia’ (p. 260).

Even though the Covid-19 crisis slowly but surely does not restrict us in our travelling behaviour and our ‘border crossings’ her defence also showed that this kind of research is still very much needed for the rethinking of the way we deal with borders, as the Dutch Immigration and Naturalisation Service (IND) did not grant her the Visum to defend her thesis live at the University in Nijmegen, 🙁

although especially academic research should by principle be borderless.

But we keep working on it…