Lately ‘Fake News’ and ‘Conspiracy Theories’ are the talk of the day. We believe that their followers are ridiculously stupid. and unknowledgeable. Some of them even believe that the result of the presidential election in the USA is a hoax which was deliberately set up by the democrats. Of course, sheer nonsense. And, Yes, we need to fiercely stand up against it. Especially science, as the rational counter programme should provide the ‘fact checks’ and propagate the truth.

Lately ‘Fake News’ and ‘Conspiracy Theories’ are the talk of the day. We believe that their followers are ridiculously stupid. and unknowledgeable. Some of them even believe that the result of the presidential election in the USA is a hoax which was deliberately set up by the democrats. Of course, sheer nonsense. And, Yes, we need to fiercely stand up against it. Especially science, as the rational counter programme should provide the ‘fact checks’ and propagate the truth.

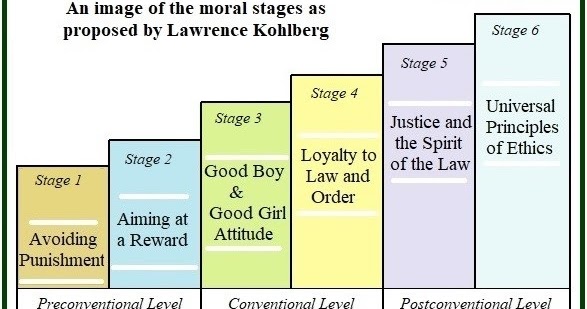

But this is where it becomes complicated: Already ages ago, in the 1950’s the expert in cybernetics, Heinz von Foerster, wrote that knowledge or on other words: that epistemology is politics. Later on, it was Michel Foucault who linked the discourse about knowledge with the geometry of power in our society. The distinction between political opinions and scientific knowledge blurs. And yes, indeed, it is generally accepted in the social sciences that science is highly political. In our research, we focus on the most urgent societal problems and try to contribute to their solution, and therefore make science highly relevant but also highly political. It is difficult to see the societal relevance of investigating black holes, but it is evident that we should find solutions for the Covid-19 pandemic, and we should try to overcome racism and poverty. But if our science is so political, what makes it different from any other political opinions? The main difference is of course that we have the better arguments. As Jürgen Habermas wrote, it is the power of the better argument, which should be convincing in a rational communicative debate. Having different opinions is not the problem, as long as we are debating with each other, as long as we exchange arguments, and are willing to put our arguments to the test, and as long as we find the words to convince the others. This is where good science can stand out; in the way, it can provide empirical evidence, in the way it can logically derive conclusions, and in the way it may underpin certain interpretations. Combined with an effective translation into everyday language, science can be a main political force and a real contribution to society.

But this is where it becomes complicated: Already ages ago, in the 1950’s the expert in cybernetics, Heinz von Foerster, wrote that knowledge or on other words: that epistemology is politics. Later on, it was Michel Foucault who linked the discourse about knowledge with the geometry of power in our society. The distinction between political opinions and scientific knowledge blurs. And yes, indeed, it is generally accepted in the social sciences that science is highly political. In our research, we focus on the most urgent societal problems and try to contribute to their solution, and therefore make science highly relevant but also highly political. It is difficult to see the societal relevance of investigating black holes, but it is evident that we should find solutions for the Covid-19 pandemic, and we should try to overcome racism and poverty. But if our science is so political, what makes it different from any other political opinions? The main difference is of course that we have the better arguments. As Jürgen Habermas wrote, it is the power of the better argument, which should be convincing in a rational communicative debate. Having different opinions is not the problem, as long as we are debating with each other, as long as we exchange arguments, and are willing to put our arguments to the test, and as long as we find the words to convince the others. This is where good science can stand out; in the way, it can provide empirical evidence, in the way it can logically derive conclusions, and in the way it may underpin certain interpretations. Combined with an effective translation into everyday language, science can be a main political force and a real contribution to society.  People will also listen to it. Take for example the currently popular crossovers between different media like in the DWDD University on Dutch Television or take the scientists who become celebrity guests in talk shows during the current Covid-19 pandemic

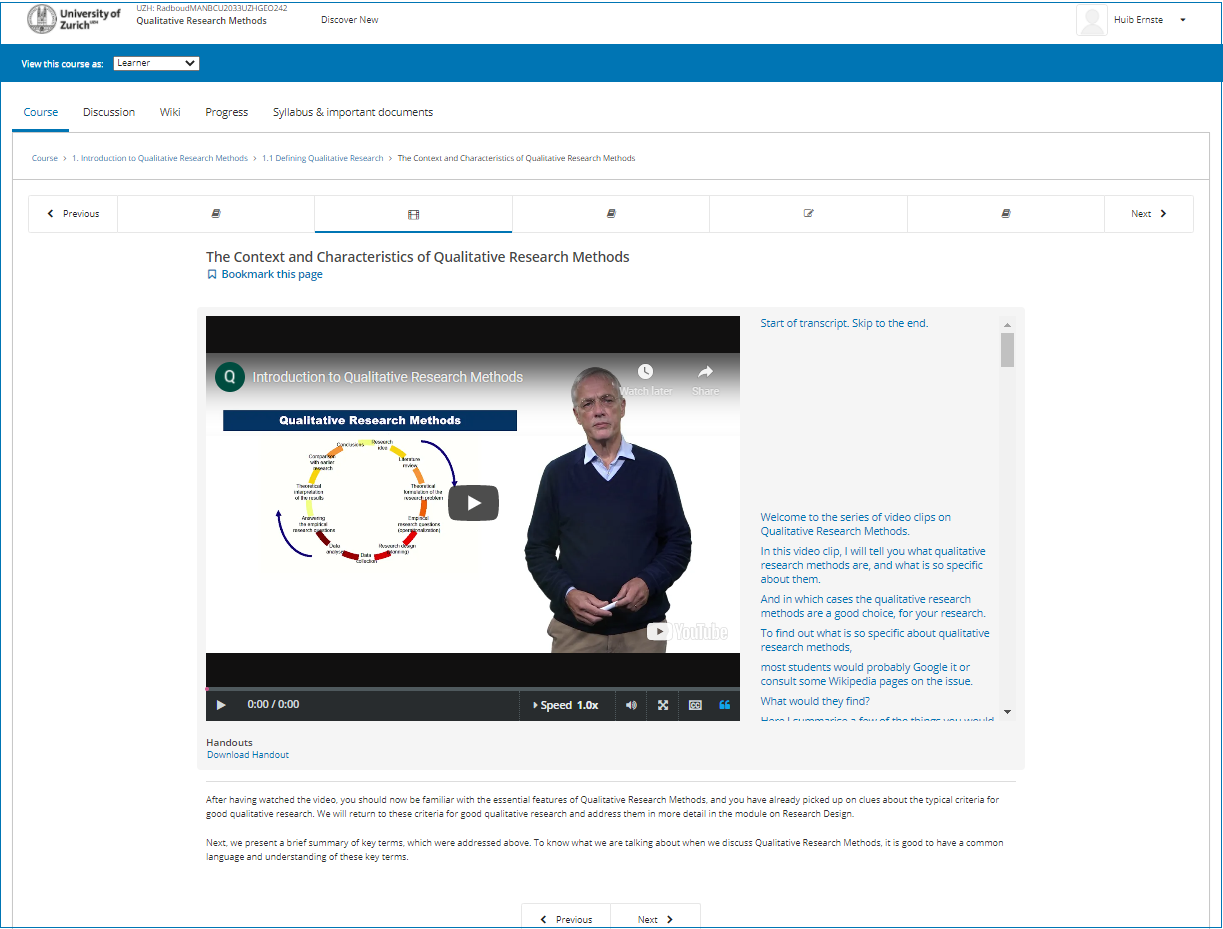

People will also listen to it. Take for example the currently popular crossovers between different media like in the DWDD University on Dutch Television or take the scientists who become celebrity guests in talk shows during the current Covid-19 pandemic . Yes, we as scientists, we should be at the front stage in many topical societal debates. We should shout out loud. This performative stage work is certainly not my personal talent (there are others in our geography group who are more talented in this respect), but we do try to raise the critical awareness of our students and we try to mobilise their societal engagement and stimulate their communicative skills to fulfil this responsible role in civil society.

. Yes, we as scientists, we should be at the front stage in many topical societal debates. We should shout out loud. This performative stage work is certainly not my personal talent (there are others in our geography group who are more talented in this respect), but we do try to raise the critical awareness of our students and we try to mobilise their societal engagement and stimulate their communicative skills to fulfil this responsible role in civil society.

However, in science one also needs to guard for being too much taken away be certain political ideals, and for not being open to alternatives ideals, ideas and arguments. Ideals are often rather simplistic categorisations of supposed ‘goods’ and ‘evils’. Idealists can easily become as autistic as many conspiracy theorists and negators of real facts. Not the difference in opinions, ideals or convictions, but the lack of scientific debate is then the problem. And each debate starts with listening, with taking the other seriously and with meeting each other at eye level. Populism is fed by classes of neglected and not-listened-to people.  They feel like the famous comic chick Calimero, who always feels as a marginalised minority confronted with a large overbearing majority. ‘They are big and I am small…’ Constructing and blaming some strawmen has always been an easy way of self-justification. But that goes in both directions. In the same way, one cannot counter populism by ridiculing it, by not taking it seriously and by not starting a discourse. This is, however, easier said than done…

They feel like the famous comic chick Calimero, who always feels as a marginalised minority confronted with a large overbearing majority. ‘They are big and I am small…’ Constructing and blaming some strawmen has always been an easy way of self-justification. But that goes in both directions. In the same way, one cannot counter populism by ridiculing it, by not taking it seriously and by not starting a discourse. This is, however, easier said than done…

Thinking of the current political situation, it seems as if science is a big exception, and is much more rational and communicative. Scientists seem to play the role of the wiser and more reasonable ones. But some critical self-reflection might be justified here. Because being at the politically correct side sometimes also gives us the illusion of truth. If we engage against racism, against colonialism, against inequality, against injustice, against climate change, or whatever, the enemy, the evil other, is easily identified and blamed. A Calimero-like reflex. But a second look can disguise this view as partly ‘fake’ and as another ‘conspiracy theory’. A closer look often shows that we, ourselves, are the so-called ‘evil others’. Such imaginary contradictions are not that uncommon in science. Science is not separate from society and its populistic tendencies. Science is always in danger of becoming a playball of the political economy of academia and of scientific populism. Also in science one sometimes observes such self recursive and self-emphasising bubbles like we also see in social media, with their own ‘truths’ and their own ‘enemies’, their own journals, their own conferences and their own fan clubs of followers and Maecenas. Science is not different from everyday life.

In this situation, scientific doubt becomes a precious virtue. The willingness to recognise and not prejudice the other and to express openness for alternatives without apriori enciphering away one’s own arguments and judgements. We need to ask who (and why) is the other and we should try to understand them. A difficult dilemma, between clearly positioning oneself while also being ready to move on to new insights and understandings, between clearly communicating what we really believe to know and interaction for the sake of gaining better knowledge. Like in society also in science the debate around this dilemma is reviving. The dilemma, however, is not just the problem, but also the solution. We should not be tied to fixed positions, to fixed categorisations, of fixed conceptualisation and essentialising judgements, but we should always be in between, on the move, in transgression, crossing borders, in a state of change. Although this blog-site has placemaking as title, scientific placemaking in this line of reasoning should focus on creating spaces for change, change of knowledge, change of understanding, change of position and change of place. Only in this way we can fight prejudice, conspiracy and populism, not just in science but also in society.

Not so long ago, one of my favourite columnists wrote a background article on this issue in the Dutch newspaper NRC Handelsblad, which I share with you here in my own freely translated version.