When we talk about placemaking, we are talking about how to create a ‘better’ place and we immediately get enthusiastic about this prospect, because we indeed experience today’s world and today’s places as subject to improvement. Geographers usually feel very engaged with the world they live in and with the place they directly experience. One of the core motives of every geographer is to be a world-changer, to reimagine our future and to really make difference. Placemaking is therefore closely related to utopian thinking.

When we talk about placemaking, we are talking about how to create a ‘better’ place and we immediately get enthusiastic about this prospect, because we indeed experience today’s world and today’s places as subject to improvement. Geographers usually feel very engaged with the world they live in and with the place they directly experience. One of the core motives of every geographer is to be a world-changer, to reimagine our future and to really make difference. Placemaking is therefore closely related to utopian thinking.

This is, however, easier said than done.

What does this utopian place look like? In what way is it different from current places? Is your imagination of this utopian place different from someone’s else imagination? And how do we get there? And once we get there, has the world then come to stand still? is such a place really ‘heaven on earth’ and our final destiny? So, how does utopian thinking drive geographers in their placemaking?

We need to delve a bit deeper into the concept of ‘utopia’. There is a large body of literature on utopian thinking (Claeys, 2020), in which ‘utopia’ is contrasted with ‘dystopia’ and related to what is sometimes also designated as ‘heterotopia’. See my brief overview below. Finally, in this blog entry I also want to distinguish this utopian thinking and these utopian placemaking practices from the way one of my favourite thinkers, Helmuth Plessner, talks about, how human beings reflect on their own situation from a ‘utopian standpoint’ as a condition for the possibility for creating better places.

The idea of utopia finds its roots in the classical ideas of the Golden Age of abundance and social equality, the Platonic notion of the ideal polity or ideal republic and the Christian depiction of the Garden of Eden or paradise. But the term ‘utopia’ was coined by Thomas More in 1516.

The idea of utopia finds its roots in the classical ideas of the Golden Age of abundance and social equality, the Platonic notion of the ideal polity or ideal republic and the Christian depiction of the Garden of Eden or paradise. But the term ‘utopia’ was coined by Thomas More in 1516.

He coined the word utopia from the Greek ou-topos meaning ‘no place’ or ‘nowhere’ (u or ou, no, not; topos, place) as a pun or parody of the almost identical Greek word eu-topos meaning ‘good place’. Later on the word dystopia was added to the vocabulary implying the opposite, namely a ‘bad place’. So the primary characteristic of utopia is its nonexistence combined with a topos, a location in time and space. At the same time, it is a place which is clearly designated as good. The latter is of course always a rather contested judgement. The eutopias one would describe as good places in the sixteenth century would probably horrify us in the twenty-first century, while the other way around, what we would describe as eutopia today, would be seen as dys-topia by the people in the times of Thomas More. Important is, that all utopias, consist of a dream of a better place, which is dramatically different from what we know as our current situation. We know these as mythical places, golden ages, Arcadias, earthly paradises, fortunate isles, or isles of the blest. As Claeys (2020, p. 1) continues, they describe places with respect to different features like e.g. security, immortality, unity, equality and egalitarianism among the people, unity between the people ad God, abundance without effort and labour, no enmity between humans and other living creatures, etc. etc. However, they do not just describe a utopian place, but they describe a radical difference in the practices and places of that age. As such, each utopia comes with its own dystopia as a contrast programme.

As a literary genre, it does not just represent a social dream or a kind of transformative plan or (revolutionary) social reform movement attempting to realise their blueprint for an imagined better future, it was also used to describe what is less utopian in some of our utopian designs, take for example George Orwell’s 1984 or Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, showing that this kind of utopias easily may turn into totalitarian horrors underscoring at the same time how unrealistic some of these ideal places are. As such they inherently represent a rather conservative tendency, distracting us from attempting to realise a more ideal place.

On the other hand, Barbara Goodwin and Keith Taylor (1982) in their book on The Politics of Utopia argue that utopia should be regarded as a political theory which allows us to describe an alternative to the here and now, as a frame of reference enabling us to criticise and to change society. A kind of relative utopia, which may not be immediately achievable, but is not intrinsically impossible, in contrast to an absolute utopia, which can never be achieved (Levitas, 2011, p. 203-204).

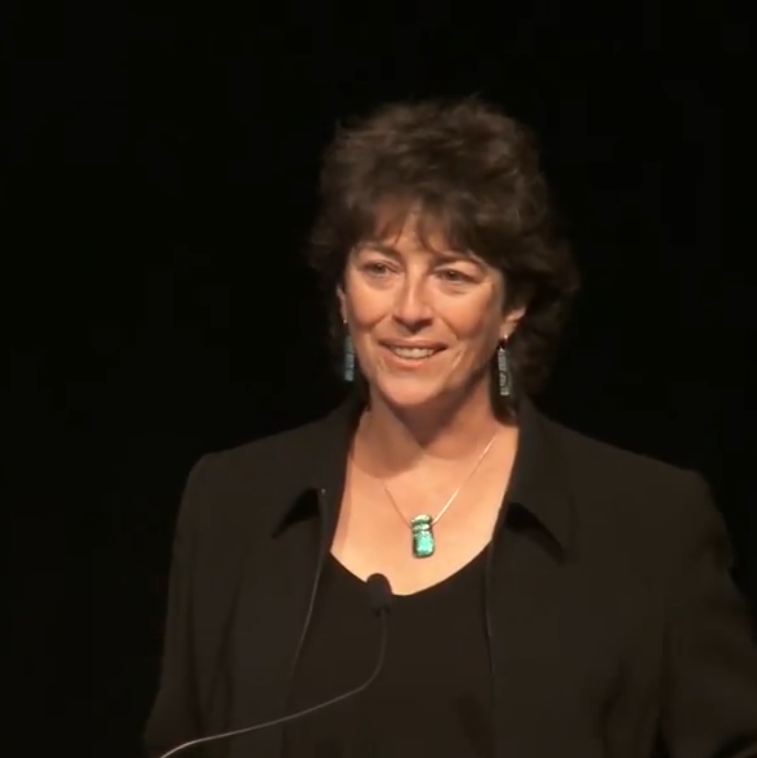

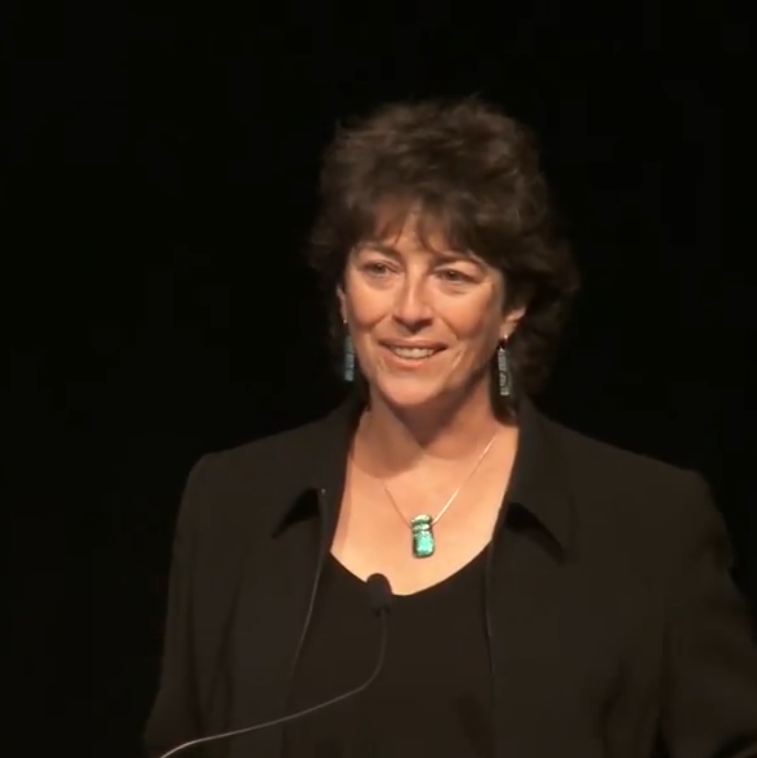

Have a look at the following extract from a presentation on ‘Utopianism in the twenty-first century’ by Prof. Lucy Sargisson, an expert on utopian thinking, about the basic terminologies in utopian thinking (click on the picture to start the video).

Have a look at the following extract from a presentation on ‘Utopianism in the twenty-first century’ by Prof. Lucy Sargisson, an expert on utopian thinking, about the basic terminologies in utopian thinking (click on the picture to start the video).

Many attempts have been made to realise utopia.

In each of these cases, utopia indeed is characterised as a place which cannot be, or as a non-place.

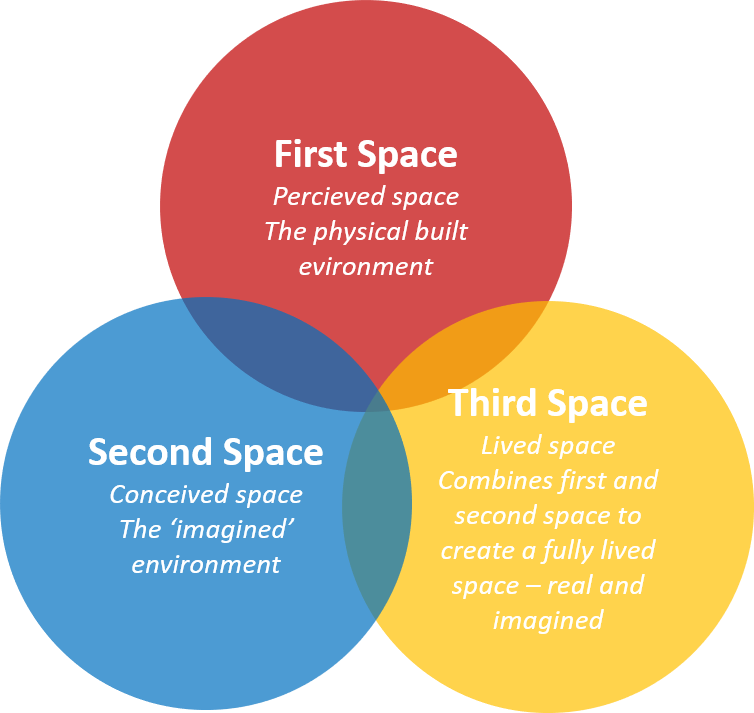

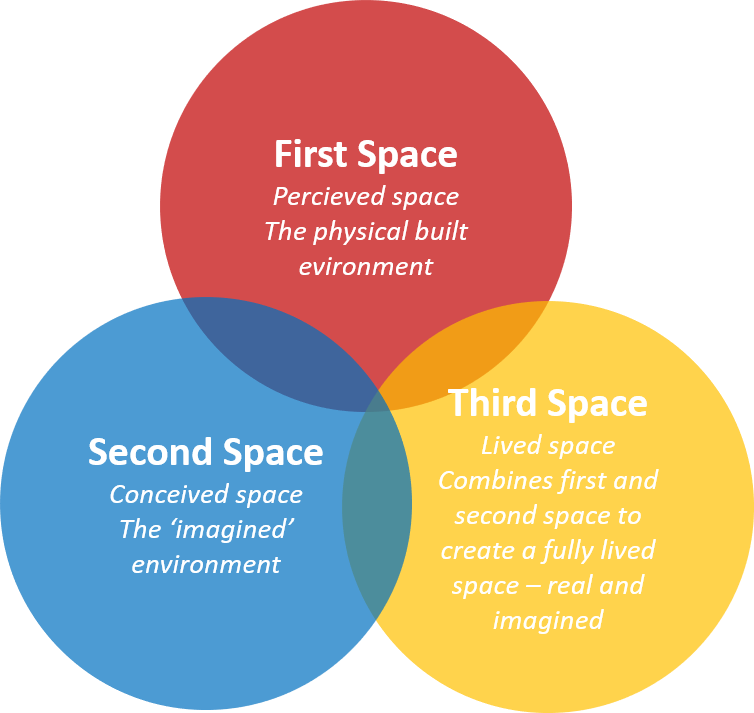

The imagination of a single ideal place devoid of tensions and inequalities, to a certain degree, also implies that these utopian places are assumed to be homogeneous and uniform. This, however, was challenged by Michel Foucault, when he introduced the term heterotopia, which he describes as places of otherness (from the Greek héteros meaning other, another, different). Foucault’s description of heterotopia has always been rather ambiguous and confusing and has provoked more debate than clarity, but was nevertheless broadly picked up and applied in many different ways and contexts (Dehaene & De Cauter, 2008). Heterotopia, in Foucault’s view, is where things are different, not equal or uniform, but different and possibly even unconnected. In some cases, these heterotopic places can be seen as places where those who are different are isolated, enclosed, put aside and out of sight, in an attempt to purify that place (Johnson, 2013) as a dystopian side-effect of attempting to create utopian places. In that sense, for Foucault, there is no utopia without dystopia, and meanings are only made through differences.  In many cases, Foucault, however, also uses the term for places in which differences are affirmed and excepted and enabled to exist together in a larger whole, as places without dominance and repression of the others in a kind of postmodern imagination. In this strain Lefebvre, Soja, Bakhtin, Jameson and others describe alternative heterotopic ‘third spaces’, or better ‘third places’ which tolerate while at the same time retaining these differences to overcome these negative side-effects. But in all cases, these places are always real existing places and never pure and utopian non-places. This way of thinking in terms of real or concrete utopias in contrast to the related dystopic other, or in terms of heterotopias became mainstream in the 1980s and 1990s, while utopian thinking became more marginalised. Instead of utopia as a promising totalising ideal, critical thinking with a clear and cursed other became the dominant mode of argumentation. Especially today we notice that critical thinking is not driven by a utopian urge, but is driven by truths and counter-truths, by facts and alternative facts, by one essentialisation in contrast to other essentialisation. We imagine ourselves in a real and concrete, self-justified utopian position, or on the road to such an undisputable ideal place. We do not conceive these places as inherently imagined and unreal, as utopian in the original sense of the word. Even if we think of them as ideal places in which we have overcome hitherto differences, differences between man and women, between nature and culture, between the privileged and the unprivileged, between now and then, between here and there, between us and them, etc. These assumed real and concrete utopias can only be defined and positioned in contrast to the implied and equally real dystopias and therefore create new distinctions, new borders, new differences, and new injustices, they cannot get rid of the heterotopic other. Each inclusion implies another exclusion. We seem to be imprisoned in a heterotopic world, in which, we cannot avoid taking a position and also take a counter-position.

In many cases, Foucault, however, also uses the term for places in which differences are affirmed and excepted and enabled to exist together in a larger whole, as places without dominance and repression of the others in a kind of postmodern imagination. In this strain Lefebvre, Soja, Bakhtin, Jameson and others describe alternative heterotopic ‘third spaces’, or better ‘third places’ which tolerate while at the same time retaining these differences to overcome these negative side-effects. But in all cases, these places are always real existing places and never pure and utopian non-places. This way of thinking in terms of real or concrete utopias in contrast to the related dystopic other, or in terms of heterotopias became mainstream in the 1980s and 1990s, while utopian thinking became more marginalised. Instead of utopia as a promising totalising ideal, critical thinking with a clear and cursed other became the dominant mode of argumentation. Especially today we notice that critical thinking is not driven by a utopian urge, but is driven by truths and counter-truths, by facts and alternative facts, by one essentialisation in contrast to other essentialisation. We imagine ourselves in a real and concrete, self-justified utopian position, or on the road to such an undisputable ideal place. We do not conceive these places as inherently imagined and unreal, as utopian in the original sense of the word. Even if we think of them as ideal places in which we have overcome hitherto differences, differences between man and women, between nature and culture, between the privileged and the unprivileged, between now and then, between here and there, between us and them, etc. These assumed real and concrete utopias can only be defined and positioned in contrast to the implied and equally real dystopias and therefore create new distinctions, new borders, new differences, and new injustices, they cannot get rid of the heterotopic other. Each inclusion implies another exclusion. We seem to be imprisoned in a heterotopic world, in which, we cannot avoid taking a position and also take a counter-position.

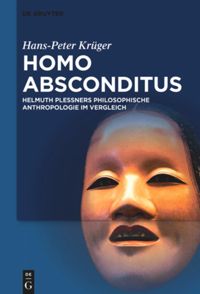

Even though many of these critical positionings intend to overcome old-fashioned categorisations and essentialisations of our human being, it is often forgotten, that in creating imagining and essentialising new real utopias, we neglect the inherent dystopian aspects of each of them. Philosophical anthropology, the discipline specialised in reflecting on what it means to be human – in the guise of the work of Helmuth Plessner, regularly quoted in this blog-site – instead came up with a conceptualisation of our human being which tried to avoid any kind of essentialisation of our specific and real human way of life while at the same time describing our inherently human being as based on the imagination of a utopian position.

According to Plessner the human being is on the one hand historically and geographically, materially and socially positioned in the real world of here and now. Plessner calls this our centric positioning. But, according to Helmuth Plessner, as human beings we are, on the other hand, also already beyond ourself and eccentrically positioned in an abstract, unreal fully inclusive utopian world. It is typically human to be caught in a dialectical relationship between our centric and eccentric position. As such, for Helmuth Plessner, the human being is essentially unessentialisable, or as he denotes it, the human being is homo absconditus. This point of view clearly pertains the difference between diverse forms of life in our world. This implies that also any kind of real utopian positioning of our human being, or human situation or way of life, needs to relativised and is inherently contingent. It needs to be thought of as a continuous becoming and re-positioning in which one can always imagine a different and maybe even ‘better’ or at least ‘different’ situation or place. These concrete positions cannot be described as a real utopia, or as an ideal home, since we as human beings simultaneously have a true eccentric utopian standpoint, beyond any qualities of our current situation. ‘[F]or behind every determination of our being lies dormant the unspoken possibilities of otherness’ (Plessner, 1999, p. 109).

According to Plessner the human being is on the one hand historically and geographically, materially and socially positioned in the real world of here and now. Plessner calls this our centric positioning. But, according to Helmuth Plessner, as human beings we are, on the other hand, also already beyond ourself and eccentrically positioned in an abstract, unreal fully inclusive utopian world. It is typically human to be caught in a dialectical relationship between our centric and eccentric position. As such, for Helmuth Plessner, the human being is essentially unessentialisable, or as he denotes it, the human being is homo absconditus. This point of view clearly pertains the difference between diverse forms of life in our world. This implies that also any kind of real utopian positioning of our human being, or human situation or way of life, needs to relativised and is inherently contingent. It needs to be thought of as a continuous becoming and re-positioning in which one can always imagine a different and maybe even ‘better’ or at least ‘different’ situation or place. These concrete positions cannot be described as a real utopia, or as an ideal home, since we as human beings simultaneously have a true eccentric utopian standpoint, beyond any qualities of our current situation. ‘[F]or behind every determination of our being lies dormant the unspoken possibilities of otherness’ (Plessner, 1999, p. 109).

Helmuth Plessner describes this typical human eccentric positionality by means of three fundamental anthropological laws: (1) the law of natural artificiality, (2) the law of mediated immediacy and (3) the law of the utopian standpoint. Through the eccentric positionality of human being he loses its natural position and pre-given relationality with the world which creates the need to enhance ourselves artificially and causes us to lose our direct relationship with our surroundings and with ourselves and experience it only indirectly, mediated through our current bodily existence and expressive positioning which is not necessarily, nor fully, intended or of our own choosing. We experience ourselves from a neutral utopian standpoint as essentially contingent and as inherently ‘deconstructive’ beings, which are in constant need to (re-)construct themselves. But instead of assuming a new real and concrete ideal utopian home, the utopian standpoint is much more radically inclusive as it does NOT attempt to define or concretise this final utopian standpoint, but assumes it as an inherently transcendental point of view without any attributes and without any exclusivity. As such it is a true utopian, non-place, or in-between place, or a place located in the nowhere. It defines a specific human openness to everybody and an openness to everything, or to any kind of ‘other’, irrespective of what kind of nature. As such, this is a strong and radical inclusiveness, which reaches beyond designs of concrete and real utopias, and which is aware of all the inherent dystopias and contingencies related to them. These presumed restricted real utopias always create new dystopian exclusions. In contrast, the utopian standpoint, which Helmuth Plessner describes as typically human, defines an inclusive ‘Mitwelt’ or ‘shared world’, as a condition of the possibility to take the perspective of the other and to adopt the moral principle of including, and recognising others as if they were one-self (de Mul, 2019, pp. 79-80; Heidegren, 2021) and the moral basis for dialogue. In this way it also relativises our own centric positioning and our own autonomy to determine our fate (Lindemann, 2014, pp. 96-104).

At the same time it also brings us further away from what we usually assume to be our ‘home’ and makes us constitutively homeless. Resulting in a utopian hope to transcend this tragic aspect of the human predicament and to find a blissful home (Plessner, IV, p 419, as quoted by de Mul, 2019, p. 81). So, this characteristically human radical inclusive utopian standpoint, does not disqualify the attempts to establish a more inclusive conception of human being in our everyday life. No, it actually conceives these attempts as necessary and unavoidable, and as the other side of the dual aspectivity of our being human. But exactly because the human being dialectically emerges in between our centric and eccentric counterparts, these attempts are both from a centric perspective positive positionings as well as from an eccentric perspective inherent failures. So, they are positive attempts to deconstruct and overcome the hitherto categorisation of our human being and attempts to create a real and more inclusive utopia, while at the same time, they are by necessity also creating new dystopian exclusions, seeking new deconstructions and even more or different kinds of inclusiveness. This kind of philosophical anthropology might serve as enlightening the attempts to create real utopias, while it also makes more explicit our human roots, which take all differences in the diverse forms of being and living in this world seriously, instead of dealing with the world only from a narrow minded real utopian point of view.

This might sound as a piece of heavy philosophising, but it is of fundamental importance for the way we think about our everyday placemaking for the sake of a better world (Schlitte, 2018).

References

Achterhuis, H. (2016) Koning van Utopia. Nieuw Licht op het Utopisch Denken [King of Utopia. New light on utopian thinking]. Lemniscaat, Rotterdam.

Claeys, G. (2020) Utopia. The history of an idea. Thames & Hudson, London.

Dehaene, M. & De Cauter, L. (eds.) (2008) Heterotopia and the City. Routledge, London.

Foucault, M. (1986) Of other spaces. Diacritics. Vol. 16, pp. 22-27.

Heidegren, C.-G. (2021). Recognition in Philosophical Anthropology. In: Siep, L., Ikäheimo, H. & Quante, M. (eds.) Handbuch Anerkennung [Handbook Recognition]. Springer, Berlin, pp. 385–389.

Johnson, P. (2013) The geographies of heterotopia. Geography Compass. Vol. 7, No. 11, pp. 790-803.

Levitas, R. (2011) The Concept of Utopia. Lang, Oxford.

Lindemann, G. (2014) Weltzugänge. Die mehrdimensionale Ordnung des Sozialen [Relations to World. The multidimensional order of the social.]. Velbrück, Weilerwist.

More, T. (2016 [1516]) Utopia. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Mul, de (2019) The Emergence of Practical Self‑Understanding. Human Agency and Downward Causation in Plessner’s Philosophical Anthropology. Human Studies. Vol 42, pp. 65–82.

Plessner, H. (1999)The Limits of Community. A critique of social radicalism. Humanity Books, New York.

Schlitte A. (2018) Place and Positionality – Anthropo(topo)logical Thinking with Helmuth Plessner. In: Hünefeldt Th. & Schlitte, A. (eds.) Situatedness and Place. Multidisciplinary perspectives on the spatio-temporal contingency of human life. Springer, Cham (pp. 137-150).

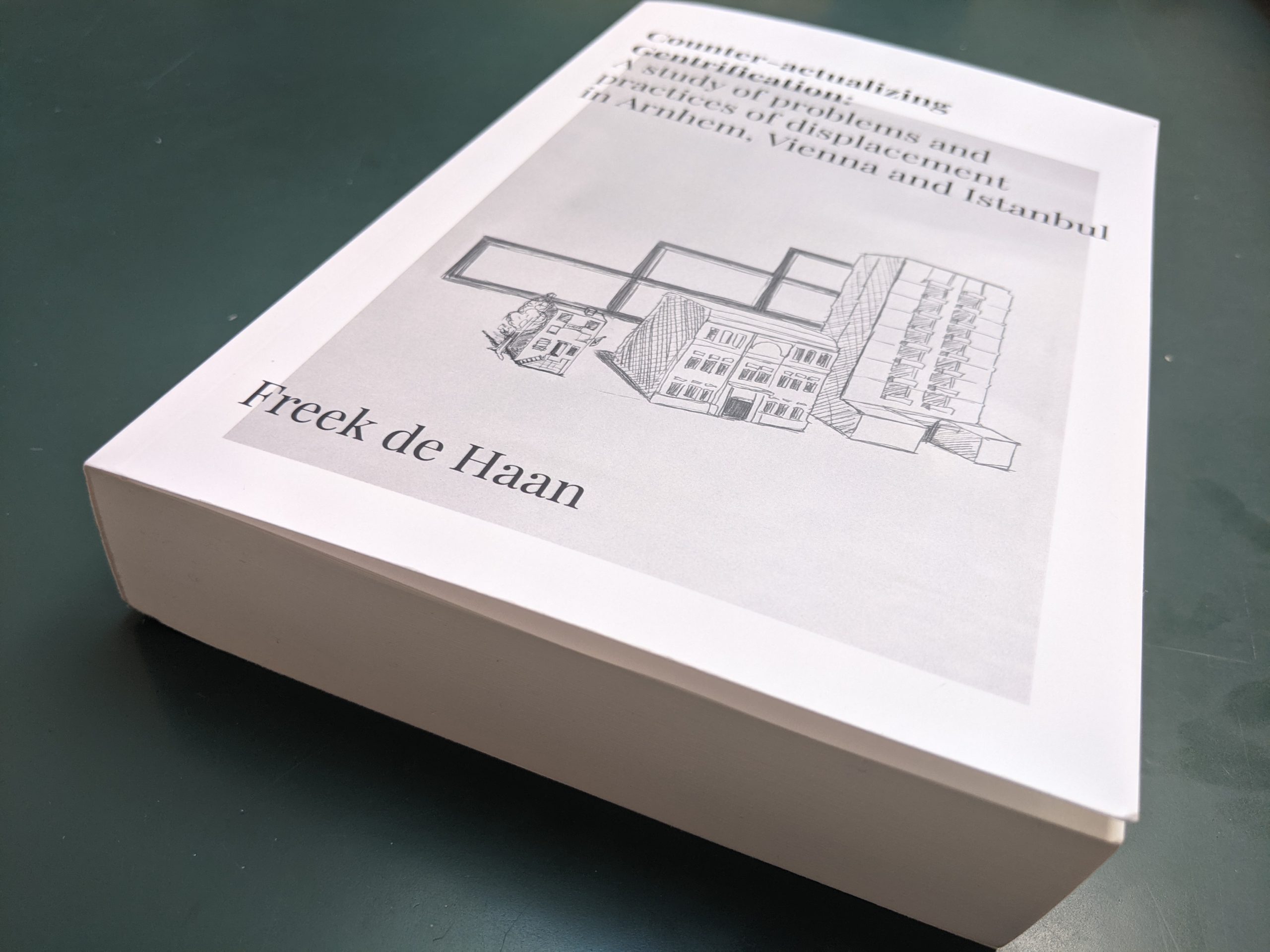

On Thursday, June 30, 2022, Freek de Haan successfully defended his PhD thesis on ‘Counter-actualizing Gentrification: A study of the problems and practices of displacement in Arnhem, Vienna and Istanbul‘ (click on the picture to download the whole thesis). Gentrification is not a new phenomenon. It has been researched for several decades already and one might wonder what new aspects can be discovered about it. Traditionally there have been two different and opposing opinions of what causes gentrification. On the one hand, there were those scholars who believed it was mainly driven by speculative capitalist interests related to the rent-gap theory. One might label these as the ‘it is the economy stupid’-camp. On the other hand, we had those who believed it was much more driven by the cultural dynamics, which made certain run-down parts of the city attractive again for specific groups of creative and better-to-do people. This might be labelled as the ‘it is the culture stupid’ camp. Much of the research on gentrification did only seem to reproduce those insights and add only marginally to radical new insights. Freek de Haan, however, tried to develop a totally new way of looking at this phenomenon. Instead of looking at gentrification with the usual concepts, he tried to trace down, how these concepts emerged and were actualised in the

On Thursday, June 30, 2022, Freek de Haan successfully defended his PhD thesis on ‘Counter-actualizing Gentrification: A study of the problems and practices of displacement in Arnhem, Vienna and Istanbul‘ (click on the picture to download the whole thesis). Gentrification is not a new phenomenon. It has been researched for several decades already and one might wonder what new aspects can be discovered about it. Traditionally there have been two different and opposing opinions of what causes gentrification. On the one hand, there were those scholars who believed it was mainly driven by speculative capitalist interests related to the rent-gap theory. One might label these as the ‘it is the economy stupid’-camp. On the other hand, we had those who believed it was much more driven by the cultural dynamics, which made certain run-down parts of the city attractive again for specific groups of creative and better-to-do people. This might be labelled as the ‘it is the culture stupid’ camp. Much of the research on gentrification did only seem to reproduce those insights and add only marginally to radical new insights. Freek de Haan, however, tried to develop a totally new way of looking at this phenomenon. Instead of looking at gentrification with the usual concepts, he tried to trace down, how these concepts emerged and were actualised in the  everyday practices on the ground in gentrifying parts of the city, and how alternative ways of looking and conceptualizing were pushed aside while continuing to loomingly be present. This did not only include the everyday practices of the different groups of inhabitants but also of the related policymakers, the real-estate entrepreneurs and associations, etc. Gentrification seen in this way is not pre-given, and especially also not in the way it performs and is assembled in the many diverse forms in the different cases investigated. This thesis tries to conceptualise the process of gentrification from a perspective mainly inspired by the work of Gilles Deleuze, to fully grasp its complexity and contingency. Taking that complexity into account, also implies that there are no simple solutions and quick fixes for the problems and opportunities related to gentrification. This was, both empirically and theoretically a grand endeavour, resulting in a 523 p. long PhD thesis, which excels in how Freek de Haan persistently and consistently applied his approach to re-construct the actualisation, or to retrospectively ‘counter-actualise’, gentrification, to derive a radically new understanding of gentrifcation. A real tour de force… for which he was honoured with a cum laude graduation.

everyday practices on the ground in gentrifying parts of the city, and how alternative ways of looking and conceptualizing were pushed aside while continuing to loomingly be present. This did not only include the everyday practices of the different groups of inhabitants but also of the related policymakers, the real-estate entrepreneurs and associations, etc. Gentrification seen in this way is not pre-given, and especially also not in the way it performs and is assembled in the many diverse forms in the different cases investigated. This thesis tries to conceptualise the process of gentrification from a perspective mainly inspired by the work of Gilles Deleuze, to fully grasp its complexity and contingency. Taking that complexity into account, also implies that there are no simple solutions and quick fixes for the problems and opportunities related to gentrification. This was, both empirically and theoretically a grand endeavour, resulting in a 523 p. long PhD thesis, which excels in how Freek de Haan persistently and consistently applied his approach to re-construct the actualisation, or to retrospectively ‘counter-actualise’, gentrification, to derive a radically new understanding of gentrifcation. A real tour de force… for which he was honoured with a cum laude graduation.

The ‘Pakhuis’ (Warehouse) was our favourite student pub for the weekends. Notwithstanding the not so fancy (but cheap) housing accommodation during my studies, we were happy with our newly gained autonomy. My first room somewhere around the Plantsoenstraat, at that time, had rather primitive sanitary facilities, with a separate toilet-building in the back garden. For a shower, we anyhow had to go to the university sports facilities. Soon I moved to downtown, in the red light district. My room was noisy and in the wintertime, I had to go to the university library to keep warm, which by the way, unintendedly was also profitable for my study results. Then we had the opportunity with some extra state subsidies to rent an apartment in a highrise building on the outskirts of the city in Vinkhuizen. For us, this was ‘luxury’, although on the ninth floor when the wind was sweeping over the flat Groninger countryside, the wind howled through the cracks, and the elevator always smelled of piss, and we had to queue up to make a telephone call at the only telephone booth in the street, in these very cheap low-end housing conditions.

The ‘Pakhuis’ (Warehouse) was our favourite student pub for the weekends. Notwithstanding the not so fancy (but cheap) housing accommodation during my studies, we were happy with our newly gained autonomy. My first room somewhere around the Plantsoenstraat, at that time, had rather primitive sanitary facilities, with a separate toilet-building in the back garden. For a shower, we anyhow had to go to the university sports facilities. Soon I moved to downtown, in the red light district. My room was noisy and in the wintertime, I had to go to the university library to keep warm, which by the way, unintendedly was also profitable for my study results. Then we had the opportunity with some extra state subsidies to rent an apartment in a highrise building on the outskirts of the city in Vinkhuizen. For us, this was ‘luxury’, although on the ninth floor when the wind was sweeping over the flat Groninger countryside, the wind howled through the cracks, and the elevator always smelled of piss, and we had to queue up to make a telephone call at the only telephone booth in the street, in these very cheap low-end housing conditions.